[This is a cross post from my article on graytier.com published on 18 Jan 16]

Intro

As penetration testers and security professionals we now have a myriad of tools at our disposal. It seems like everyday a new product, program, or script is being released to make our jobs easier and increase our effectiveness (ok that’s debatable :). However, with all of these tools available how likely is it that most testers are taking the time to understand what’s going on behind the scenes? Arguably the most well-known penetration testing tool-suite is Metasploit. Thanks to all the hard work from the community and Rapid7 the Metasploit Framework is an amazing resource at our disposal. I’ve heard some complaints of Metasploit lately, but in my opinion there’s still nothing quite like it available. Now, we all know that it’s bad practice to download an exploit from an untrusted website and throw it at a system without proper vetting, but it’s equally important to understand the inner workings of tools you trust like Metasploit.

In this post I’m going to briefly touch on how to exploit CVE-2015-2342 with Metasploit, but mostly I want to focus on the indicators of compromise (IOC) that are left behind. I’ll also show you how to cover your tracks and remove these IOC, but there’s always a chance you left some trace behind. To be clear, I’m using Metasploit to make a point because of its popularity; this isn’t a critique.

CVE-2015-2342

For those of you that are not familiar with CVE-2015-2342 the best way to describe the vulnerability is to quote the NVD:

“The JMX RMI service in VMware vCenter Server 5.0 before u3e, 5.1 before u3b, 5.5 before u3, and 6.0 before u1 does not restrict registration of MBeans, which allows remote attackers to execute arbitrary code via the RMI protocol.”

In the most basic sense this means that an attacker can upload a malicious JAR to a vulnerable vCenter server and obtain code execution by invoking methods in that JAR remotely. This is possible because the JMI RMX service has been configured to not require any authentication. In Java-land I’m being a bit sloppy with my terminology since technically it’s an MBean, but I’m not going to cover the nuances of a Java in this post.

Exploitation

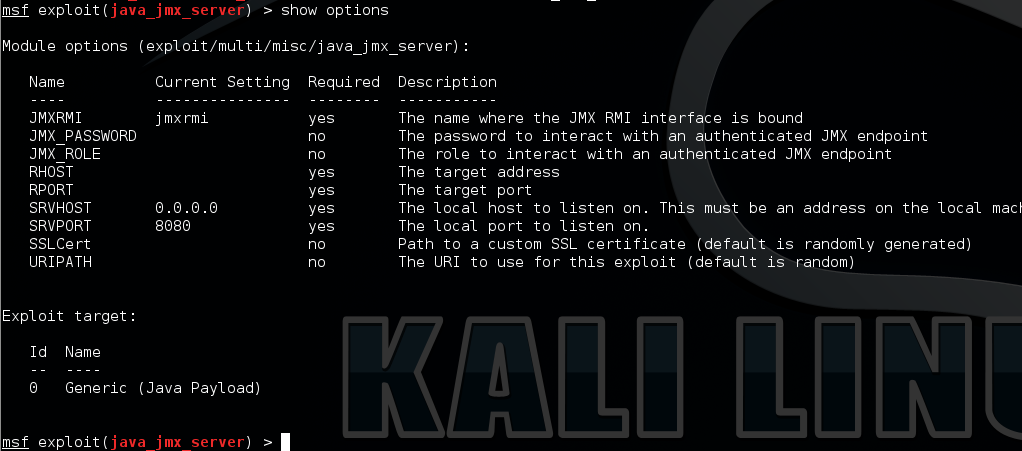

To exploit a known vulnerability you have two choices – you can roll your own or use existing code. A really good explanation of the technical details around this type of vulnerability can be found here, and there’s no reason to re-hash that information. Most of us don’t have the time to write a new exploit for every vulnerability we come across so we rely on tools we trust to help us out. In this case we can use the exploit/multi/misc/java_jmx_server Metasploit module to exploit a vulnerable server.

Now all you have to do is fill in the options as usual and type exploit. With a bit of luck you should have a shell on the target system running at a high privilege level; on Windows this should be NT AUTHORITY/SYSTEM. So far this is nothing new. Most pen testers can fire off a Metasploit module, but it’s the artifacts you just left on that system that I want to go over? As a side note, I would also like to mention that the Metasploit payload was failing on some systems we tried, but more on that later.

Behind the Scenes

What happens after you type exploit? As noted in Braden Thomas’s article, in order to upload a malicious Mbean you have to host two resources – an MLet and a JAR. Since the remote JMX console doesn’t require credentials we can then “ask” the vCenter server to load our malicious payload by invoking a method called getMBeansFromURL. This method takes a string variable specifying a URL as its only argument. Once invoked getMBeansFromURL kindly requests our payload from our local server and loads it for use on the target. Then it’s just a matter of remotely triggering our payload which, in this case, Metasploit has stuffed into the JAR. If you decided to roll your own version of this exploit the steps are the same, and you can make the payload whatever you like. Ultimately it doesn’t matter though. We’ll come back to this.

IOC

At this point you probably either have a shell, or if you’re like us the payload failed. There’s a lot that could go wrong here. We made sure to test this out in a lab so we could troubleshoot any strange behavior, but ultimately we couldn’t narrow down exactly what was stopping our Metasploit payload from calling back. After some investigation we saw that Java was throwing an exception when the payload was triggered, but rather than dig through Metasploit payload code we ultimately wrote our own exploit. Which brings me to the main point of this article – we didn’t get a shell using the Metasploit module, but just attempting left a number of artifacts on the target system.

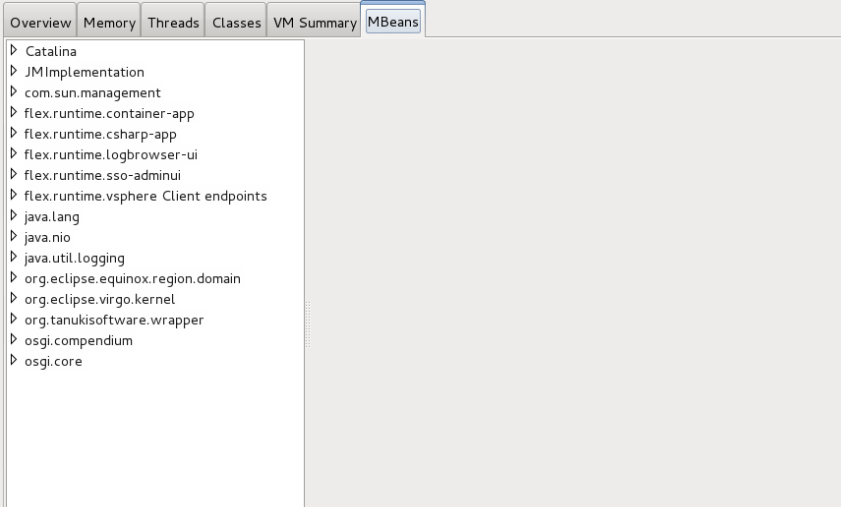

If you connect to the target with JConsole you can plainly see a number of items that look out of place. Lets look a before-and-after of the JConsole

JConsole before exploit attempt

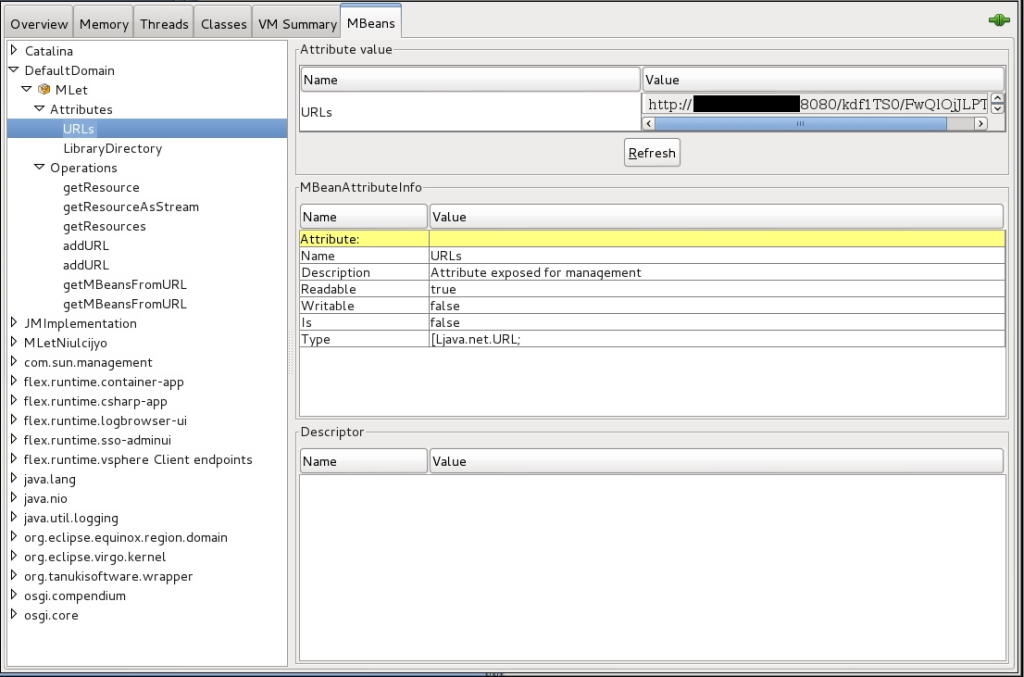

JConsole after exploit attempt

The first noticeable indicator you can see is the MLetNiulcijyo MLet now in the list. If you’re following along at home this name will vary because the name is just MLet concatenated with a random string. Strings like this are very Metasploit-ish. Randomly generated strings are used throughout the framework in one way or another. Expanding this MLet you can also see it contains an object called jmxpayload, and under that you can see it exposes a run method that can be invoked remotely. Network defenders take note that if you’re looking at a production system and see this, now is the time to spin up you IR procedures.

You can also see a new entry, DefaultDomain, has appeared towards the top of the list. This alone is not necessarily an IOC. However, expanding this field you can see we have an MLet sub-directory and further expanding reveals Operations and Attributes sub-directories. Under the Operations directory we see the most helpful getMBeansFromURL method exposed, but the main IOC I wanted to point is under the Attributes ->URLs path. Clicking on the URLs attribute clearly shows the IP of our attacking machine! Obviously, this is likely a pivot point because no one has this service exposed to the Internet right? Anyway, as far as IR is concerned it doesn’t get much easier than this to find the next host to investigate.

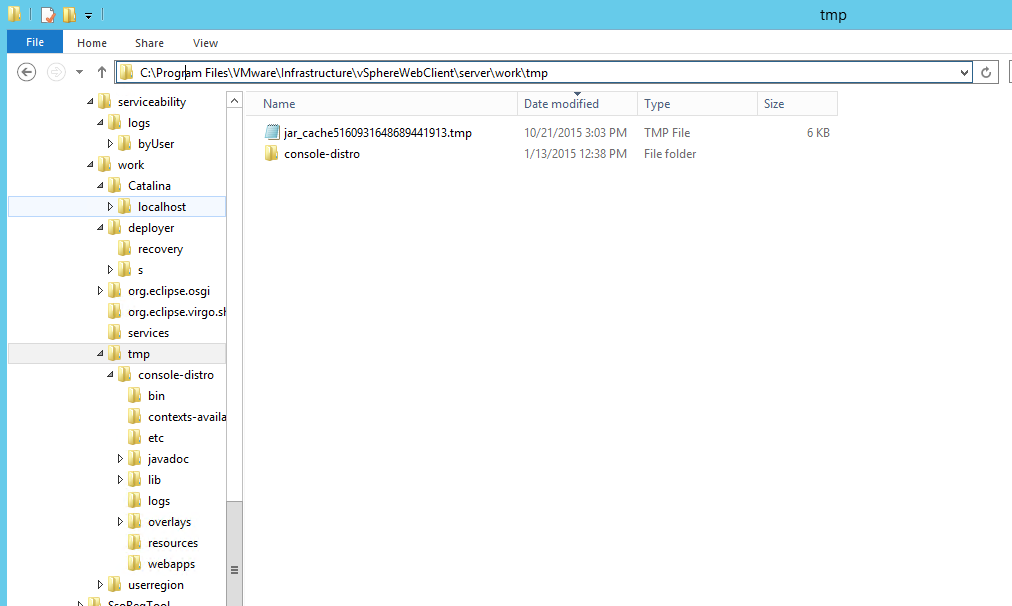

As a responder the next question you should be asking yourself is what’s in that payload? Well it turns out that the entire JAR is copied to a temp directory on the vCenter server. A file I’m sure your forensic team would like to have a look at. In our lab the JAR was contained at the path below:

C:\Program Files\VMWare\Infrastructure\vSphereWebClient\server\tmp

If you’re part of an IR team, at this point, you can be fairly certain that a Metasploit module has probably been fired at this server. Although I want to stress that these IOCs are not Metasploit specific – they are exploit specific! If you rolled your own version of this you’re still likely to see the DefaultDomain and another new MLet appear in the list.

Covering your tracks

You can try to cover your tracks by either modify the Metasploit module to make the MLet look less noticeable (e.g. rename your payload to MLetText or something like that) or create your own version with different names and methods. Regardless, you’re still going to have similar artifacts on the target system. The only difference is you’ll be making it slightly harder for admins and incident responders to find you. Although, as far as I can tell, the DefaultDomain MLet will always be created and point right back to you. So with all this in mind how do we cover our tracks? Well, thanks to some research by @ruddawg26 it turns out that all you have to do is restart the vspherewebclient service to wipe the slate clean. You already have SYSTEM level access on the server so using the net command on Windows should be sufficient. Of course the downside to this method is that restarting a service could show up as a red flag in the event logs, but it certainly makes it harder to track you down.

Conclusion

Know your tools. In this case Metasploit was working exactly as advertised. Pen testers it’s your job to know what your tools are doing. Even if you trust the source it’s important to know what affects you’re having on a target system. Defenders if you see any of these IOC on your vCenter servers you need to be worried! CVE-2015-2342 is a serious vulnerability that can be fixed relatively easily. No one should be getting owned by this vulnerability at this point in the game. Lastly, keep this in mind when you’re hiring penetration testers or Red Teams. Maybe a previous assessment left these artifacts on your network, but the only way to know is to spend the time and money going through the IR process after the fact. Make sure you’re picking the right team.