This is a companion blog post to my talk last month at NoVAH on two methods I used to generate keyboard walks for password cracking.

Quick Links:

Main repo: https://github.com/Rich5/Keyboard-Walk-Generators

Motivation

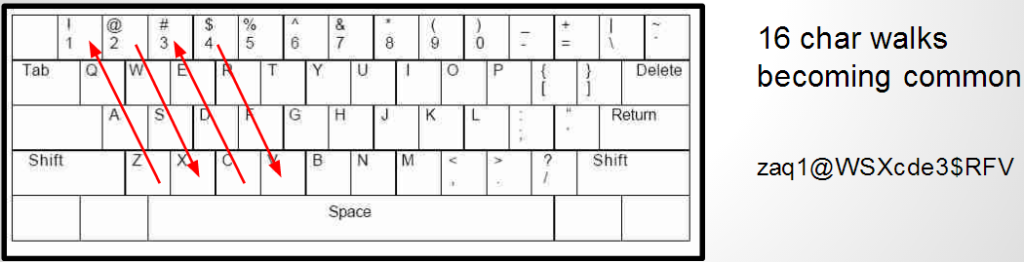

A somewhat common trend is to use keyboard walks in an effort to produce complex passwords. This isn’t a new trend by any means, but I have noticed a lot more walks showing up in Mimikatz outputs lately. My theory is that complex password policies are actually encouraging some users to use walks, and who can blame them really? If the policy states that you must have a password at least 12 characters, comprised of upper and lower case letters, and include numbers and special characters then keyboard walks are an easy solution. My goal was to show my clients that using keyboard walks is not a good security practice, and that they can easily be cracked with a simple dictionary attack; however, the problem I ran into was that finding a good word list wasn’t as easy as I thought. To be clear, I did find a few lists and generator scripts, but they often missed what I considered to be common walks. So in the end (and to my own dismay) I decided to generate my own list of keyboard walks. If you’re in a rush and just looking for the solutions I used then jump down to the “Methods” sections of this post.

NOTE: For my purposes I needed a list generated from the qwerty english keyboard although the methods outlined below can be used for other layouts.

Background

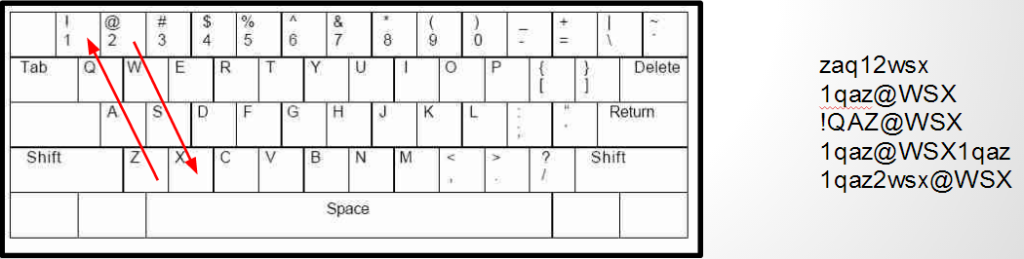

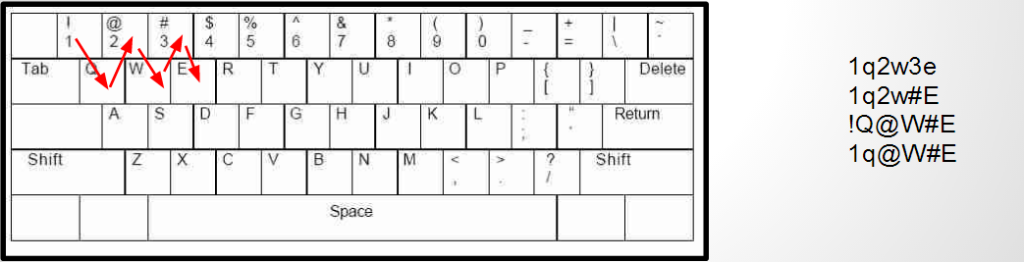

When I’m referring to keyboard walks what I really mean is using visual patterns on the keyboard to generate strings. Just to get everyone on the same page let’s first take a look at a few examples.

One of the main problems that struck me when I started this project is how do you programmatically “know” which keys are next to one another? The qwerty keyboard was basically created through trial-and-error to prevent typewriter hammers from getting stuck together; other than that there really isn’t any rhyme or reason to the layout. The rest of this post describes two methods that I used to generate keyboard walks. Method 1 is more academic whereas Method 2 is more practical for password cracking.

Method 1: Tree Walks

Steps:

- Create directed graph representing the qwerty keyboard

- Walk the graph using a modified Depth-limited search (DLS) recording each path

To create a directed graph data structure, unfortunately, I had to type one out by hand. The entire data structure is a python dictionary of dictionaries where each node is a letter that acts as the outer dictionary key, and edges are keys to the inner dictionary. A small example of one letter is shown below:

'S': {'diag_down_left': 'z',

'diag_down_right': 'c',

'diag_up_left': 'q',

'diag_up_right': 'e',

'down': 'x',

'left': 'a',

'loop': 'S',

'right': 'd',

'shift_diag_down_left': 'Z',

'shift_diag_down_right': 'C',

'shift_diag_up_left': 'Q',

'shift_diag_up_right': 'E',

'shift_down': 'X',

'shift_left': 'A',

'shift_loop': 's',

'shift_right': 'D',

'shift_up': 'W',

'up': 'w'},

You can see the entire data structure at https://github.com/Rich5/Keyboard-Walk-Generators/blob/master/Method%201%20-%20Tree%20Walks/qwerty_graph.txt

Once I had a data structure to parse I used a modified DLS to walk the tree and record the path along the way. Below is the pseudo code for walking the tree.

TARGET_DEPTH = X

for each node in graph {

path = “”

depth = 0

DLS(node, depth, path)

}

DLS(node, depth, path){

path.push(node[value])

if depth >= TARGET_DEPTH {

print path

} else {

depth = depth + 1

for each edge on node {

DLS(graph[edge], depth, path)

path.pop()

}

}

}

Here’s a quick visual demo of what this algorithm is doing

All source files for this method can be found on github. QwertyTreeWalker.py takes the following arguments:

usage: QwertyTreeWalker.py [-h] [-l [L]] [-p [P]] [-x] [-H] [--stdout]

[--noplain]

[file_name]

Generate walks for Qwerty Keyboard

positional arguments:

file_name File with adjacency list of format {'letter':

{'direction': 'letter connected'}}

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

-l [L], -length [L] Walk length

-p [P], -processes [P]

Number of processes to divide work

-x, -exclude Will trigger prompt for link exclude list

-H, -hash Output NTLM hash for testing

--stdout Output to screen

--noplain Do not print plain text hash

Running the following command:

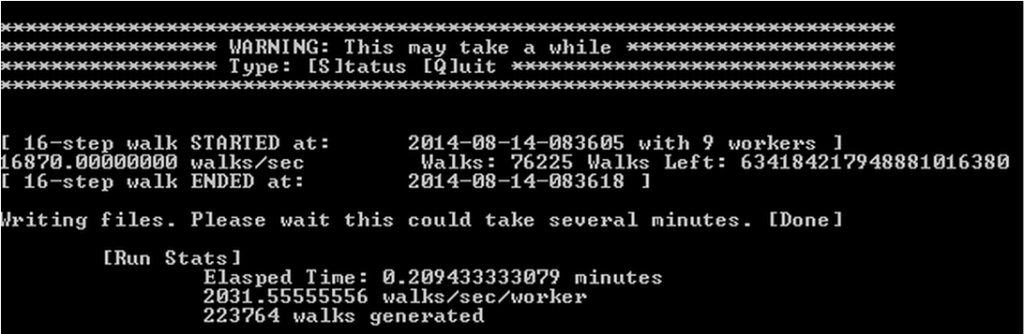

python QwertyTreeWalker.py qwerty_graph.txt -l 16 -p 8

will bring up an interactive prompt similar to what’s shown below

Running in default mode the tree walker script will generate one or more output files containing keyboard walks for each process. If you would like to print to stdout then use the –stdout command line argument.

One major thing to note here is the shear number of walks that would be produced by this method. In fact, on the system I ran the above command the script would not finish in my lifetime. Even generating walks of length 8 would take more than a month. Here are some quick calculations on run times based on walk length.

| L | Total Walks | Estimated Time (avg 15K walks/s)* |

| 4 | 548,208 | ~1 min |

| 5 | 9,867,739 | ~ 10 min |

| 6 | 177,619,388 | ~3.2 hrs |

| 7 | 3,197,149,049 | ~2.5 days |

| 8 | 57,548,683,002 | ~44 days |

| 16 | 6.3418422e+20 | way too long!! |

*Using 8 processes on Intel i7-2600 @ 3.40GHz

I tried pruning the tree to get the run times down, but it was still taking way too long for my purposes. Even though Method 1 was interesting, since I wanted a word list up to length 16 obviously this wouldn’t work. So after making some assumptions about how real users would create keyboard walks I ended up using Method 2 for all practical purposes.

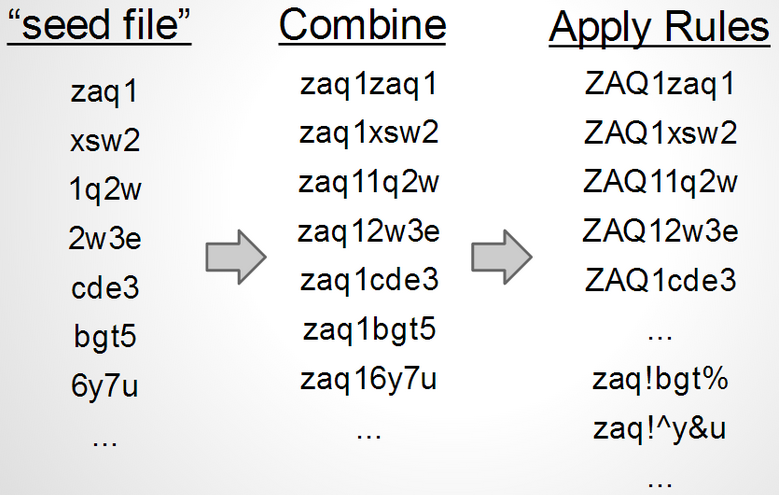

Method 2: Combinator Script

Steps:

- Create a “seed file” of small qwerty walks

- Combined contents of seed file with itself to generate longer walks

- Use mutation rules to make up for any missed walks

The “seed file” I created was just a simple list of 4 character walks that I hand typed. I tried to come up with all the walks that I would possibly use based on the keyboard layout. I then combined the seed file with itself to generate 8 character walks, and again to get 16 character walks. I purposely made my seed file simple knowing that I was going to use a ruleset to make up for the missed characters. Below is an overview of the process.

Again all the source files can be found on github. I found the best results are to use the following commands to generate a 5GB file.

python Combinator.py 4_Walk_seed.txt -l 8 > 8_Walk.txt<br /> python Combinator.py 8_Walk.txt -l 16 > 16_Walk.txt

You can then input the 16_Walk.txt file into your favorite password cracker with the companion rules file.

Final Thoughts

While interesting, Method 1 turned out to be more of an academic exercise. Method 2 turned out to work better than I thought for several reasons. One, I believe that this word list will crack a majority of the most commonly used walks. Two, the travel footprint is very small. The seed file, combinator script, and rules file combined are less than 4KB. It only takes 5 minutes to generate a 5GB file which means that I don’t have to carry around another massive dictionary on remote engagements. Finally, it turns out that Method 2 catches walks that Method 1 won’t. Method 1 assumes that walks only use adjacent keys, but in reality users will try to get creative and jump from one column or row to another. As always I hope someone finds this useful. Let me know if you have any questions.